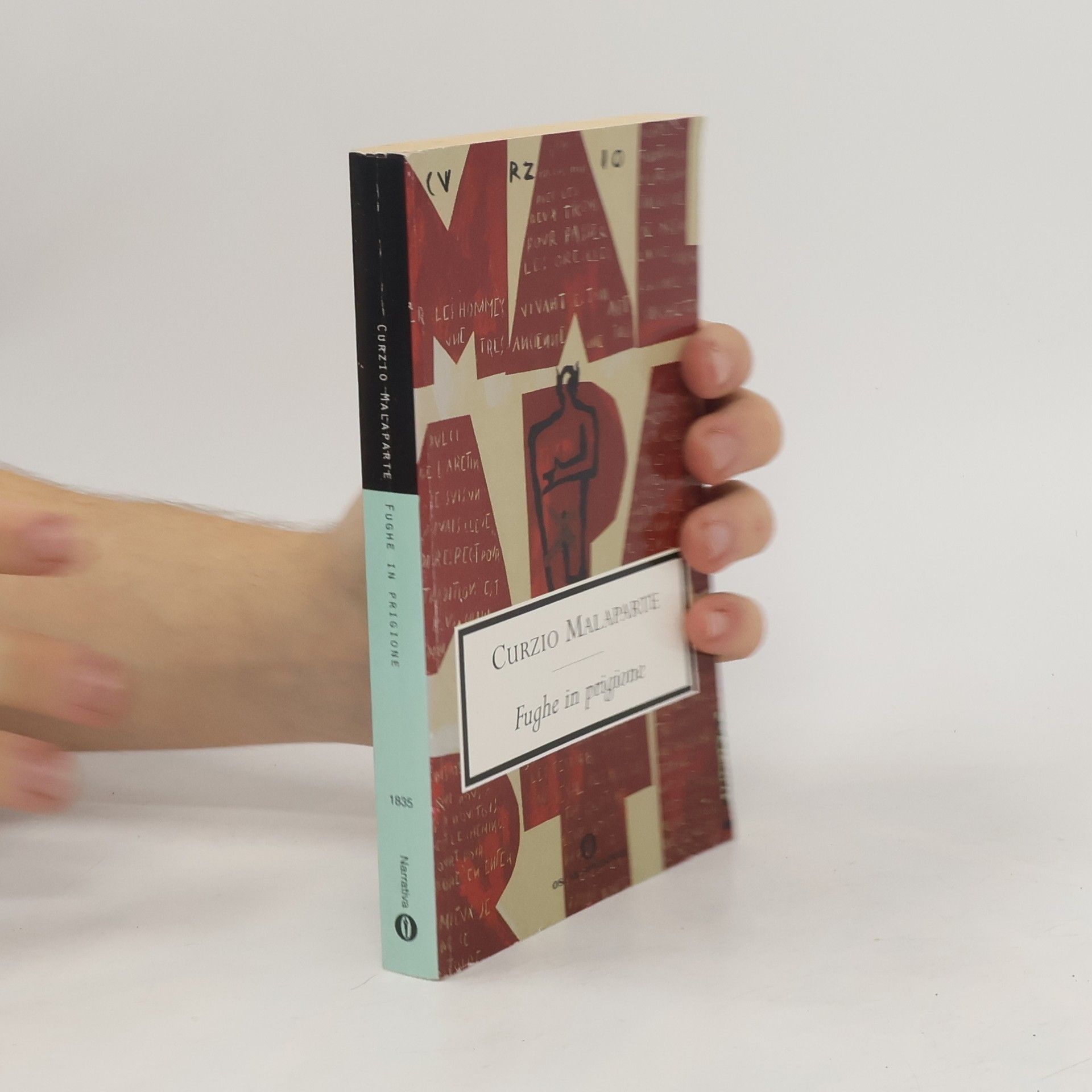

Fughe in prigione

- 289pagine

- 11 ore di lettura

Pubblicate in varie edizioni, nel 1936, nel 1943 e, infine, nel 1954 (quella qui riproposta), queste "Fughe in prigione" sono state scritte durante i periodi trascorsi da Malaparte nel carcere romano di Regina Coeli e al confino di Lipari, dove venne inviato per i suoi atteggiamenti liberi, provocatori, non allineati al regime fascista, che anzi attaccò violentemente. A queste pagine del tempo di prigionia Malaparte volle aggiungere alcuni testi scritti in Francia e in Inghilterra poco prima dell'arresto. Si tratta di memorie, riflessioni di carattere culturale, studi letterari nei quali l'autore sembra cercare un rifugio e una via di fuga per lo spirito.